“Death reveals that truth and absurdity are one.” --Zygmunt Bauman (Lock, 202)

In Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death Margaret Lock traces the development of the concept of brain death as the “new death” in North America and Japan (2). Lock is interested in the ways in which the theoretical and social discourse and clinical practice of the new death have been alternately accepted and resisted in the two contexts and the intimate relationship between the politics of organ donation and transplantation and the existence of this relatively new classification. Lock poses many questions in her investigation: What is death? Is it biological, social, or personal? Is it a definitive moment or a process? “Does the “vital principle” of life reside in, or is it produced by, a single organ or part of a single organ...or is the “soul” represented throughout all organs, tissues, and cells? That is, does death occur and unique “personhood” end when a small number of organs, or perhaps only one, permanently cease(s) to function, or must the entire organism go through such a process before death is defined?” (74). More specifically, how did the functional integrity of the brain come to be the marker for passing into the abyss of the unknown? How have our bodies and their parts become alienable, exchangeable commodities, and what does their value in death reveal about their value in life and the delicate negotiation of the boundary between the two?

Lock spends some time detailing the historical confluence of events that preceded the definition of brain death as the “new death” in North America. Among other factors, she notes the roughly concurrent development of intensive care technology (specifically the artificial ventilator) that allowed medical professionals to keep otherwise “terminal” patients alive for longer periods of time and the increasing success rates of experimental organ transplants and specifically the first successful heart transplant in 1967 (3). This close chronological relationship creates new questions. As Lock points out, “when the ventilator becomes the simulacrum for the defunct brain stem and its activities, unsettling ambiguities arise about ‘which signs of life are sufficiently important that their loss constitutes the death of the patient while other signs of life persist’” (74). Furthermore, a new classification of “brain death” allows for the procurement of organs for transplant from previously anomalous “living cadavers” (1). For the skeptical, “the concept of ‘brain death’ remains incoherent in theory and confused in practice. Moreover, the only purpose served by the concept is to facilitate the procurement of transplantable organs” (358). Indeed, “the phenomenon of chronic BD [brain death] implies that the body’s integrative unity derives from mutual interaction among its parts, not from a top-down imposition of one ‘critical organ’ upon an otherwise mere bag of organs and tissues. If BD is to be equated with human death, therefore, it must be on some basis more plausible than that the body is dead” (360).

Yet, as Lock notes, “the existence of the technology does not determine anything” (40). Although the technology now exists to artificially prolong the signs of life in patients who are categorized as (brain) dead, “it is not itself a decisive force in the formation of discourses and practices in connection with the brain-dead” (ibid). After all, as Lock points out, the technology and clinical expertise exists as well in Japan, but there brain death has by and large not been accepted as death. Lock offers several reasons for this discrepancy, among them the differing moral economies and narratives of personhood in the two places. What interests me most, however, is her assertion that “a sharp dichotomy between life and death is biologically artificial because death is a process rather than an event. There is no detectable moment of death, and therefore the concept must be socially agreed upon” (361). Because medicine operates very much within the social and cultural spheres, it is essential that the new death be accepted not only within medical discourse but social discourse as well.

Lock contends that “the majority of us raised in the dominant traditions of Europe and North America understand death as an unambiguous, easily definable point of no return” (4). While there has certainly be some vocal resistance to the new death in North America (both among physicians and laypeople), the majority of people have come to understand that defining point as when the brain ceases to function. She asks, “why did we in the ‘West’ accept the remaking of death by medical professionals with so little public discussion?” (ibid). While I most certainly recognize the value of Lock’s ethnographic analysis, I wish to consider these questions through a slightly different lens: the popular cultural representation of monsters and, specifically, zombies. Lock suggests that “an awareness of mortality is the ultimate source of cultural creativity” (201). While she is referring more here to the imaginative discourse of science, I argue that the artistic fascination we have with these “monsters” is indeed evidence of our anxieties about the ambiguity of death and the particular location of personhood, and thus the meaningful line between life and death, in the brain. As such, media representations of the zombie can be understood as part of the “pornography of death” (204). “Death, its representation, its discourses, and performance haunt society, and death frequently becomes a site from which the social order is contested” (195, emphasis mine).

What is a zombie? Zombies, of course, are a very real social phenomenon in places like Haiti (see Wade Davis’ The Serpent and the Rainbow) and West Africa, where the ancestors of many present-day Haitians originally lived. In the Haitian context, a zombie is someone who has been brought to the brink of biological death, having been administered a psychotropic poison that reduces the signs of life (heart rate and respiration) so much so that even prominent “Western” doctors consider the person dead. The person is then essentially buried alive and later exhumed, administered an antidote and taken off into zombie slavery. There is an elaborate epistemology of personhood that makes this all possible (I won't get into it here, but there are five different parts to the person, and the theoretical process of zombification relies upon affecting some but not others because otherwise actual death could occur). What I think is fascinating about the Haitian practice of zombification is the way in which it relies upon the imitation of biological death but actually serves to enact social or personal death. The person may still be alive technically, but their personhood has to some extent been extinguished. Zombification, according to Wade Davis, is inherently a social process, and families and communities are intimately involved in its execution. In Lock's terms, the society allows for the "commodification" (quite literally in terms of slave labor) of certain people/bodies who have transgressed its laws in some way (9).

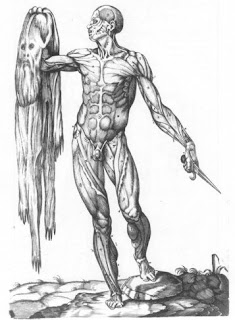

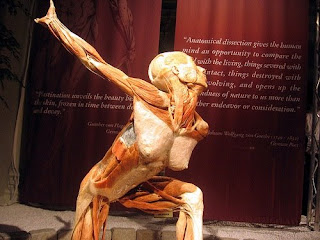

The way that the zombie functions as a symbol in our culture, however, is mostly as an exoticized and culturally appropriated distortion. But there are some definite similarities to the Haitian referent. Dictionary.com defines zombie as “a person whose behavior or responses are wooden, listless, or seemingly rote; automaton” (http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/zombie). We also conceive of zombies as lacking consciousness or will, and visual depictions often show them with collapsed or disintegrating skulls, suggesting a similarity to the “anencephalic monster” infant (354). Lock offers that these children are treated as “nonhuman” because it is believed that they “never have thoughts, feelings, sensations, desires, or emotions” (ibid, 356). This seems to be precisely what makes both the infant and the zombie monstrous. And yet there is also the added compulsion of the pop culture zombie to eat human flesh and particularly the brain, perhaps to compensate for the absence of its own. As Lock writes, “When the brain is gone the void opens up, swallowing all meaning and value, unless resurrection can be negotiated” (207). Clearly she means this in another context (the “gift of life” narrative of organ donation), but it seems equally fitting in discussing zombies.

As it turns out, 1968 was both the year that the Harvard Committee announced its definition of the “new death” and the year that George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead was first released. It has since been remade multiple times and ignited a whole zombie film genre, testifying to the persistence of the zombie in our cultural imagination. Lock writes, “Brain death discourse has certainly been legitimized by positing death as the dualistic Other of life--as an irreversible, final event. Possibilities of movement between the world of the ‘lively’ and the domain of the ‘becoming dead,’ and occasional reversals of this process, are excluded from this discussion” (206). But the possibility of movement between death and life is very much alive in narratives of the “living dead.” Furthermore, the zombie discourse also reveals the fear of contagion at the heart of our feelings about death. Lock cites Robert Fulton when she writes, “we react to modern death as we would to a communicable disease--a condition about which we must be vigilant because in theory it might be avoided even though contagious” (201). The threat of the zombies in films like Night of the Living Dead is that they want to make us one of them. Could we read this anxiety as representative of a socially repressed fear that the medical profession's greater inclusivity in defining death somehow threatens us?

Perhaps one of the most memorable iterations of our zombie fascination is Michael Jackson's music video Thriller. The sheer production and spectacle at work in the video is astounding. Thriller also frames the threat of the zombie as one of contagion. Vincent Price "raps" in conclusion, "And though you fight to stay alive/Your body starts to shiver/For no mere mortal can resist/The evil of the thriller" (http://www.lyricsmode.com/lyrics/m/michael_jackson/thriller.html). Interestingly, there was some recent buzz on YouTube when a video surfaced of inmates at a prison in the Philippines performing Thriller as part of an exercise program. I think this example is fascinating. Here you have prison inmates, whose personhood has already been extinguished to a certain extent through incarceration by the State, pretending to be zombies, who are themselves imagined as devoid of personal interest.

This example once again brings the element of power (political, medical, and cultural) into our discussion. I found the image of a zombie Uncle Sam recruiting to prepare for an imagined zombie attack to be illustrative in this regard. What nationalistic agenda can be implicated in the emergence of the "new death" and the possibilities for organ procurement and transplantation it creates? Since Uncle Sam himself is a zombie in this image, we might also ask who the true monsters are in the debate over brain death. Are they the anencephalic infants and brain dead patients? Or are the monsters the doctors who do the dirty work of cutting off life support and/or cutting into "living cadavers?" Or is the monster the modern medical establishment that seeks to reduce the value of human life to the proper functioning of the brain? Is the monster Dr. Frankenstein or his creation? Maybe modernity itself is monstrous in the way it presents us with these irreconcilable problems?

Lock posits, “This dilemma cannot be resolved. Knowledge about the brain will expand, and ICU technology will become more effective, but these changes will not dispel the fundamental problem that the determination of biological death of an individual can never be definitively reduced to a point in time, no matter which criteria are applied” (361). According to Ruth Oliver who herself came back from a brain dead diagnosis, “the value of each human soul created transcends what doctors can or cannot test of the functioning of the brain” (363). Norman Fost is a bit more pragmatic in his assessment: “I believe it is helpful and desirable to select a point in time where it is appropriate to say , ‘He is dead,’ not because it is true, or because we are expert on such questions, or because it facilitates organ retrieval, but because it is helpful” (362). I am struck by the paradox of our inability to accept death (the compulsive desire to prolong life even if the added duration is brief and the quality of that life is poor) and the simultaneous expansion of the definition of death (from the cessation of function in the heart and lungs to brain death) that allows us to actually designate more people as dead in order to use their organs to delay death in others. We expand death in order to attempt to transcend it. Is this just a desperate stopgap measure? Is this biomedical quandary simply the secularization of the Christian resurrection narrative? Since we have lost the possibility of the afterlife, are we trying to perpetuate our lives as infinitum? I don't have the answers to these questions. But as long as this paradox exists, I think we will continue to see anxiety over what counts as alive and dead, human and monster, played out in the popular creative imagination.

Works Cited

Davis, Wade. The Serpent and the Rainbow. New York, NY: Simon & cShuster, 1997.

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/zombie

http://www.lyricsmode.com/lyrics/m/michael_jackson/thriller.html

Lock, Margaret. Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Images and Video (In Order of Appearance in Text):

http://www.fearwerx.com/images/Fulci_zombie.jpg

http://media.photobucket.com/image/zombie%20attack/therock21223/4360478_147524bd49.jpg

http://www.wayodd.com/funny-pictures2/funny-pictures-zombie-survival-kit-1cs.jpg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gUKvmOEGCU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1kNP3jogfek

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hMnk7lh9M3o